In 2020/2021 Coraline Jortay (PhD in Languages, Literature and Translation Studies, ULB), was granted a Wiener-Anspach postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Oxford, where she undertook a research project entitled “You, (Un)gendered: Literary Fates of China’s Most Popular ‘Useless’ Pronoun (1927-1956)”, under the supervision of Dr Jennifer Altehenger (Faculty of History). In September 2021, while stopping by in Brussels, she granted us this fascinating interview on her work as a researcher and a translator.

In 2020/2021 Coraline Jortay (PhD in Languages, Literature and Translation Studies, ULB), was granted a Wiener-Anspach postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Oxford, where she undertook a research project entitled “You, (Un)gendered: Literary Fates of China’s Most Popular ‘Useless’ Pronoun (1927-1956)”, under the supervision of Dr Jennifer Altehenger (Faculty of History). In September 2021, while stopping by in Brussels, she granted us this fascinating interview on her work as a researcher and a translator.

How did you become interested in Chinese studies?

I first got interested in Chinese translation, because I had the chance, when I was in secondary school, to take Chinese evening classes at the Université de Liège. I really wanted to go on with translation and Chinese studies, and so for me the next best step at the time was to go into translation and interpreting in what was then the Institut supérieur de traducteurs et interprètes (ISTI, now part of the Université libre de Bruxelles). After that I really wanted to get into literary translation, so I worked for two years in the private sector while trying to pursue literary translation. I started working with a few publishers such as L’Asiathèque in Paris. I always had in the back of my mind to do a PhD in either translation studies or literature. While I was working in literary translation I had faced a lot of issues dealing with the translation of gender – how do we translate gender from languages such as Chinese, in which you can play with all sorts of ambiguities because grammatical gender marking is less salient, whereas French is the epitome of grammatical gender marking. Just at that time the ULB was setting up a team of East Asian Studies (EASt), which is now the Maison des Sciences humaines. A former colleague asked me whether I wanted to come back to do a PhD. So that’s the backstory!

After your PhD you were granted a Wiener-Anspach fellowship to carry out a research project in Oxford, entitled “You, (Un)gendered: Literary Fates of China’s Most Popular ‘Useless’ Pronoun (1927-1956)”. Can you tell us a little more about it?

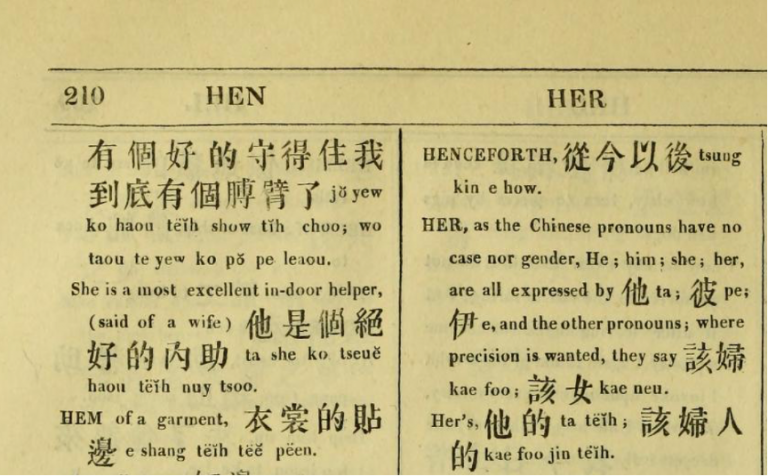

To give you a little bit of background, I did my PhD on the “invention” of gendered third-person pronouns in Chinese, because the pronouns that we use today for the feminine and neuter are only one century old. Prior to that one could of course express gender in Chinese, but the translational equivalent to he/she/it didn’t exist. I traced the social and intellectual debates surrounding that invention, with a lot of people saying it would be an inconvenient to printing press, others saying it was against gender equality because men and women would be put in different boxes. By the end of my PhD I realized that if I wanted to see those debates through I had to go all the way not until the thirties, as I had originally thought, but through the first simplification reform of the Chinese characters in the mid-fifties. My project for the Wiener-Anspach fellowship was to take the research questions I had examined for the republican era (1912-1949) and extend them into the early period of the People’s Republic China.

Robert Morrison, A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts, Part III (Macao: Printed at the Honorable East India company’s press, 1822), 210. Source: University of Westminster

What stage is your research at now?

While in Oxford I worked on primary sources from the 1950’s for the postdoc project and at the same time reworked my PhD thesis into a book manuscript, because I thought that those projects were very much interlinked. I’ll probably need another six months to finish the first draft of the book, because I still need to go to Germany to get to certain primary sources, which I couldn’t do because of Covid last year. But there were lots of wonderful resources at the Bodleian and in the United Kingdom more broadly, like primary sources related to the Chinese National Association for the Advancement of Education, and of the Committee for the Reform of the National Language.

How would you describe the experience of working in such a different academic context?

It was a little bit odd at first because I arrived amid the Covid pandemic, but my colleagues at the Oxford China Centre were absolutely wonderful. During the winter months of Covid we would even have walking meetings outside around university parks, where we would stay two meters away from each other but still have a meeting.

You also took part in the launch of the Southern Lives Network. Are there any updates about this network?

The kick-off conference is happening in Oxford in December. This is very much dealing not with the main project with the Wiener-Anspach but with my other academic interest that developed from my applied translation activities. It has more to do with contemporary postcolonial literature – in my case, contemporary Taiwanese literature. It allowed me to build bridges not only with scholars of postcolonial literature in Oxford but also with Justine Feyereisen, who works on those topics but for Francophone literature.

How does your translation activity keep feeding into your academic research and vice versa?

My translation activity is not exactly related to my research, in the sense that I translate mostly contemporary literature from Hong Kong and from Taiwan, and my main research is mostly on the Republican period in China, so early 20th century to mid-20th century. However, the interesting thing for me is that translation is one of the closest readings that you can do of any text, so that helps develop a sense for the language. Also, the authors I’m translating often deal with colonial topics. For instance, I have an offshoot project on simplification of characters in Taiwan during both the Japanese colonial era (beginning of the 20th century), and then in the 1950’s after the Kuomintang arrived in Taiwan. The contemporary author I’m translating describes how those debates impacted indigenous people in Taiwan.

A final question about your future projects, which you will be able to carry out in Oxford.

Yes, thanks to a three-year position at The Queen’s College, with three terms of archival work in Taiwan. I’ll be finishing my monograph project this year and then, if things go well with Covid, next October I should be able to go to Taiwan, get all the primary sources for the next project and then go back to Oxford for the third academic year, in 2023/2024.

What will be the topic of this new research project?

The new project deals with how Chinese characters being conceived as hieroglyphs throughout the late 19th century in European orientalist literature impacted the linguistic debates in China. For instance, ideas of whether an alphabetic script was more “modern” than other kinds of scripts weighted in debates on whether or not Chinese characters should be abolished. I’m also interested in how these debates also travelled when Chinese scholars went toward South-East Asia and described Southeast Asian scripts such as the Jawi script from Malay or body tattooing practices of indigenous people in Taiwan. There was this whole debate on different scripts being backwards or not, on what was a “modern” script, how one should define linguistic modernity and how very much colonial linguistics, translation, and linguistic debates intersected around those issues.